New Bullitain

On June 1, 2018, Michael B. Sutton, a four-decades plus veteran of the music industry who has worked with Kanye West/Jay-Z (Guess Who's Back) Michael Jackson, Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder and more, launches The Sound of L.A. entertainment company with a mission to reestablish the sound of the city. Beginning life focusing on music and records distributed via Orchard/Sony, The Sound of Los Angeles will ultimately include periodicals publishing, video and other ventures.

“The Sound of LA came to me after realizing the diversity of musical styles in Los Angeles,” states CEO Sutton. “I’ve always felt that Los Angeles has a distinctive sound that was palpable from when I first arrived here in the mid-`70s from Oakland. A few months ago, I realized that the artists I am currently working with represent that diversity - Ethnical, Magical yet Original.”

Artists in the initial rollout of The Sound of Los Angeles are the following:

Dionyza – Female Urban Pop singer: first single, “If it Kills”

Drivetime – Jazz sextet from Philadelphia led by percussionist Bernie Capodici: first single, “Mysterious Life” (instrumental)

STeaDY – Rapper from Oakland: first single, “Usual”

Mitchell Coleman, Jr. – Bassist currently promoting his third CD, Gravity CD: current single, a cover of Michael Jackson’s “I Can’t Help It” featuring former New Edition lead singer, Ralph Tresvant

R.J. Wilson – Gospel singer akin to Luther Vandross: single, “I Found You”

Lady Aneessa – Dance/Club artist from Europe: first single, “Shake it”

Why don't we know yet what killed Prince?

By Jen Christensen, CNN Updated 8:08 AM ET, Wed April 27, 2016

(CNN) We might not know what killed pop superstar Prince for weeks or even months. And while forensic science-themed TV shows make it look quick and easy, and the technology has improved, modern death investigations take time.

Prince's last days: Health scares, thrilling shows, purple pianos

Prince's last days: What we know

The Midwest Medical Examiner's Office in Ramsey, Minnesota, performed the autopsy on the 57-year-old musician on Friday. Dr. A. Quinn Strobl finished the procedure in four hours, according to the office, but Strobl won't declare what caused Prince's death until after the office gathers all the relevant details.

In a case like this, the medical examiner's office does a routine but complicated kind of detective work that relies on reaching out to family members and doctors to gather medical history and understand what prescriptions the person was taking. The office might examine the scene of the person's death. It will send tissue samples out for lab tests, and it will want results reconfirmed. And this investigation happens in offices that typically juggle dozens of cases at once.

"When 'Star Trek' is real, you'll have a tricorder that can determine what happened to someone immediately, but it doesn't work that way yet," said Kevin Lothridge, CEO of the National Forensic Science Technology Center. "The technology is a lot faster than it used to be, but there has to be quality assurance in the lab to corroborate what you may have found in the field."

Who decides fate of Prince's music 'vault'?

Who decides fate of Prince's music 'vault'? 01:57

'A very detailed process'

Prince was found unresponsive in an elevator at Paisley Park, his home and studio in Chanhassen, Minnesota, on Thursday. Paramedics performed CPR but were unable to revive him.

He had been sick with the flu earlier in the month, according to the Atlanta venue where he postponed a couple of recent concerts. His plane also made an emergency landing after his rescheduled concerts the week before.

Though Carver County Sheriff Jim Olson doesn't believe that the death was suspicious, the department decided to process the scene "because this was an unwitnessed death of a middle-aged adult," he said. "That is also normal protocol. It is not different from what we normally do."

RIP, Prince: Why we mourn the days the music dies

Mourning Prince, Michael Jackson and other music icons

If a person is killed by something obvious such as a knife or gun, or if the person is older or has been sick with cancer, the medical examiner may determine cause of death quickly. When there are no obvious signs of trauma or suicide, the medical examination may be much more involved.

In Prince's case, the medical examiner's office decided to run a full toxicology scan that could take weeks. Toxicology tests are typically what takes the longest to run in a death investigation.

"It is a very detailed process that cannot often be done in a few hours or a few days or even a few weeks. More involved investigations can take several months," said Bruce Goldberger, a professor and director of toxicology at the University of Florida College of Medicine. "By now, the medical examiner probably knows or has a pretty good handle on the cause and manner of Prince's death, but you have to do all these other tests that are a part of an investigation to officially certify the cause and manner of death."

What examiners look for

What does it mean to die of 'natural causes?'

What does it mean to die of 'natural causes?'

In an autopsy, an examiner will gather a number of samples from a body to test. Blood will be drawn from a variety of areas. A scientist might also take gastric contents, bile, liver, hair, nails or samples from the person's eye.

A scientist will first test a person's blood using something called an immunoassay to look for commonly used legal or illegal drugs. These initial toxicology tests can determine whether someone has taken something innocuous, such as allergy medicine or antidepressants, or something like opiates or amphetamines. Blood tests can also help determine whether someone died after being exposed to something in the environment, such as carbon monoxide or pesticides or some kind of heavy metal or inhalants.

If the tests come out positive for a drug, the lab runs further tests to make a definitive determination as to whether that particular drug caused the person's death.

If someone were taking an opiate, for instance, these tests can determine exactly what kind and possibly how much. If the person were using something like fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opiate that has increased in popularity and has been linked to a growing number of deaths, it can be "an enormous challenge for the toxicology lab" because it comes in a variety of formulations, Goldberger said. The initial lab might need to send it to a specialist, taking even more time.

New clue in the death of Prince

New clue in the death of Prince 02:50

If you've ever had to pass a drug test to get a job, you know that a lab can quickly figure out whether you've been using drugs by testing your urine. With a dead person, urine might not always be available. Even if it is, urine might not always tell a scientist what was going on at the exact time of death or at the time it was collected, since it takes time for the body to eliminate drugs through urine.

Scientists might examine liver samples since that organ helps your body metabolize most drugs and other substances, such as alcohol. Even if a toxicologist can't find the drug in a person's blood, it may turn up in the liver.

Join the conversation

See the latest news and share your comments with CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter.

Scientists might look at stomach contents to see whether a person recently ingested a drug; undigested pills could still be in their system. They might test the vitreous humor, the clear substance in eyes, for drugs or alcohol. Drugs can also show up in hair and nail samples.

"I know sometimes families are anxious for results, because they are waiting for death benefits or for peace of mind, but this process is a legal, multifaceted process," Goldberger said. "You want results that can be relied on and be as definitive as possible."

Don't Call Copyright A Government-Granted Monopoly

by David Newhoff

When most people discuss or debate copyright’s value in the contemporary market, they talk about the utility of the law—typically arguing the efficacy or rationale of specific contours like term length or enforcement—while generally overlooking the philosophical principles that led to the IP clause being written into the U.S. Constitution in the first place. This is of course not uncommon with any number of issues. A particular constituency or individual citizen with a political agenda is apt to read the one sentence or phrase in our elegantly concise Constitution and interpret it as he sees fit. For instance, the Framers will often allude briefly to a rationale with a dependent clause like “In order to maintain a well-regulated militia …” which is then interpreted as either a still-relevant or now-obsolete explanation for the 2nd Amendment, depending on whether the interpreter supports or refutes gun rights.

Similarly, the conditional expression setting up the IP clause, “The Congress shall have the power to promote the progress of Science and useful Arts …” has been the source of heated argument that copyright’s utility is clearly in the service of society; and this premise then becomes the basis for describing copyright as a “rent”, “tax”, or “monopoly”, granted somewhat reluctantly by the government to individual authors (and inventors) in order to extract the fruits of their labor for the greater good.

In fact, a few years ago, Mike Masnick riled up his readers at Techdirt over the fact that Register of Copyrights Maria Pallante had the nerve to suggest that copyright serves the author first and society second. Oh, the screaming and the gnashing of teeth that ensued. But, of course, from a utilitarian perspective, Pallante was making a perfectly innocuous statement of fact about the only way in which the order of operations can be applied. Clearly, if the author does not first create, society is never served at all. But that’s not what I want to talk about.

I recently finished a new book, written primarily for legal scholars, by Randolph J. May and Seth L. Cooper of the Free State Foundation, called The Constitutional Foundations of Intellectual Property: A Natural Rights Perspective. The book makes a case for the philosophical underpinnings of intellectual property in the U.S. Constitution, beginning with the Enlightenment influences on the Framers and concluding with those principles ultimately being expressed in the post-Civil War amendments ending slavery and affirming the rights of citizens regardless of their state of residence.

Terry Hart’s latest post on Copyhype is a review of this book, in which he rightly points out that the Natural Rights foundation for intellectual property has been largely substituted by a purely utilitarian discussion among most academics critical of contemporary copyright. And these murmurings in the hallowed halls of law colleges have trickled down into the blogosphere where they have coalesced around the meme that copyright is a government-granted monopoly. But to ignore the philosophical precedent for intellectual property—regardless of the necessity to debate the utilitarian contours of the laws themselves—is a tragically flawed mistake for any citizen to make, no matter where he or she sits on the political spectrum. And this is because the intellectual property right is really just one branch on a rather important philosophical tree to which all our favorite civil rights are also attached.

As mentioned, May and Cooper’s book is written by academics for academics, though it is entirely accessible to any reader, if constitutional scholarship on intellectual property is your cup of post-revolutionary tea, so to speak. But in simple terms, the first part of the book supports the view that the appearance of the intellectual property clause in Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 8 of our Constitution is an expression of the principles articulated primarily by English philosopher John Locke in his Two Treatises on Government. First published in 1689/90—exactly a century before the first U.S. Copyright Act—these treatises imagine the individual in a hypothetical State of Nature in order to then express what Locke sees as the purpose of entering into the social contract we call the state or government. In the State of Nature (i.e. a condition in which the individual enjoys what we call Natural Rights), Locke argues that the individual has a “property in his own person” and that part of the purpose of government is the security of his property, which is more commonly known by Americans as the pursuit of Happiness.

Locke uses the word property in a much broader sense than we generally to use it today, which is to say that each of us has a property in our being—our bodies, our minds, and our faculties. We still believe in this principle, of course, we just don’t generally use the word property to talk about it. But from this Lockean notion of property comes the idea that if your hands and mind are yours, then what you produce with your hands and mind—whether it’s a harvest of wheat or a novel—is logically also yours. Critics of intellectual property will often bypass Locke’s definition of the word property in order to draw contemporary attention to the logic that physical property like a car is fundamentally different from intellectual property like a copyright in a song. This argument carries particular weight in the digital age when copies of intellectual works are now profoundly non-physical; but as May and Cooper point out, the differences between these types of property are appropriately reflected in the contours of the laws themselves—and remain amendable according to changes in market and social conditions—while the foundational principles for both types of property remain sound and relevant.

The Lockean notion of a property right in the fruits of one’s labor should not, in my opinion, ever be relinquished to the authority of the government as a privilege—which is what a monopoly technically is—rather than asserted and protected as an expression of our Natural Rights as individuals. As May and Cooper demonstrate, both physical and intellectual property act to define and limit the role of government, which is entirely consistent with American constitutionalism, whereas fostering monopolies is anathema to those principles. Government’s mandate to protect both types of property, the authors argue, acts as a hedge against “centralized decision-making,” which is to say a society that is not composed of free-thinking individuals. There is no question that May and Cooper approach their argument for the foundation of IP from a libertarian/conservative perspective of limiting the power of government; and this is actually refreshing inasmuch as I have never quite understood those academics of the same political stripe, who have lately portrayed copyright as a government-granted privilege. That seems to me like surrendering considerable ideological territory in a way that is inconsistent with the advocacy of limited government.

At the same time, for those of us who lean more politically left, I would add that I believe the fruits of one’s labor principle also acts to limit the power of capital, which is particularly relevant today when so many people are frustrated to the point of concluding that capitalism is only capable of producing wealth consolidation, a foundering middle class, and corporate control of government itself. In the same way that I would advocate fixing capitalism rather than throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater, I would point out that the fruits of one’s labor concept—as it is specifically expressed through intellectual property—really implies a much larger social contract than the incentives of copyright and patent holders.

The idea that your labor is your own until you provide its fruits in fair trade to someone else is the basis of every hard-won labor and civil right—because these rights are often intertwined—over the worst abuses of either corporate owners or government agencies. This is also consistent with the views of the Founders, who sought to foster neither an intrusive government nor a new nobility that would give rise to new forms of feudalism. And because too little of the former provides opportunity for the latter, and vice versa, it is our fate to constantly seek to balance these opposing forces. Hence, the fruits of labor right vested in every individual citizen acts as a balancing force against both extremes; and IP rights are merely one specific expression of this much larger principle. Even free speech itself is an extension of this Lockean principle that the individual has a property in his person.

With 1% of the population owning more than 50% of the nation’s wealth; with direct assaults on labor rights in certain regions and economic sectors; with technologies threatening to devalue human work in various ways; and with extreme examples of certain corporate owners getting away with imposing their own morals on employees, this is a terrible time to be calling intellectual property a government granted monopoly. I would never want to cede the logical conclusion of that argument, to suggest that every citizen’s right to the fruits of his or her labor is in any way a privilege, which may be argued away on the basis of apparent utility alone. Ultimately, we’re talking about a human right that was forged in the crucible of a century and a half of English civil strife over religion and the divine right of kings. It may be just a short sentence in the Constitution, but it has a long and bloody intellectual pedigree.

Jeff Golub Passes Away at 59

From Jeff Tamarkin of jazztimes.com

Jeff Golub, a guitarist who crossed seamlessly between jazz, blues and rock, died today, Jan. 1 following a lengthy illness. He was 59. The precise cause and place of death have not yet been reported but Golub had experienced a series of physical setbacks in recent years that ultimately caused him to no longer be able to perform. First, Golub gradually lost his eyesight in June 2011 due to the collapse of an optic nerve. The following year, he fell onto the subway tracks in New York and was dragged by a train, but was rescued by onlookers and escaped unscathed. He was later diagnosed with more serious, at first unidentified, issues later determined to be a rare and incurable brain disorder called Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP). Fans contributed tens of thousands of dollars toward his medical expenses via crowd-funding websites and an auction.

Jeff Golub, who was born in Copley, Ohio, April 15, 1955, played his first gig in 1967 at age 12 and turned professional during the following decade. He studied at the Berklee College of Music and worked in singer James Montgomery’s band while in Boston. In 1980, after moving to New York, Golub joined the band of rock singer Billy Squier, with whom he toured and recorded extensively. Golub released his first solo recording, Unspoken Words, for Gaia Records in 1988.

Golub released more than a dozen albums in all as a leader and three with the Avenue Blue Band, and spent several years (1988-95) in the band of singer Rod Stewart. He also collaborated with dozens of artists as a sideman, including Ashford and Simpson, Alphonse Mouzon, Kirk Whalum, Mindi Abair, Everette Harp, Peter Wolf, John Waite, Vanessa Williams, Gato Barbieri, Bill Evans, Rick Braun, Tina Turner, Dar Williams, Brian Culbertson, Gerald Albright, Henry Butler, Jon Cleary, Marc Cohn, Richard Elliot, Robben Ford, Sonny Landreth, Jeff Lorber and Peter White. Golub was also a member of Dave Koz and the Kozmos, the house band of The Emeril Lagasse Show.

Golub’s final album, made with keyboardist Brian Auger, was Train Kept A Rolling, its title inspired by Golub’s subway incident.

Here's a peek at Golub's awesome way with a guitar...

A fitting eulogy for a fine man and player by Mindi Abair

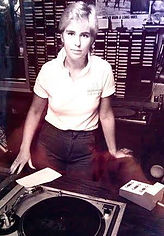

Sandy Shore SmoothJazz.com founder shares harrowing experience

Writen by Sandy Shore

from a Facebook post 10/20/2014

What you're looking at here in this picture is a 20-year-old DJ standing over her turn table riddled with bullet holes...

On October 21, 1983 I was pulling the overnight shift on KWAV FM in Monterey, California. Spinning music made me really happy, I didn't care it was the middle of the night. This night was like any other night and while I noticed a van parked out on the street by the radio station, I really didn't give it a lot of thought.

2: 51 AM I began playing Men At Work's "Who Can It Be Now" and the music was suddenly stifled by the sound of gun shots at the front door of the radio station. I wasn't sure what I was hearing honestly... thought it might be an axe or baseball bat based on the way the door was flying off the hinges. Regardless, I ran back to the booth... to make sure that the song didn't run out. I was trained properly...

I had my record already cued before the disruption, wait for it... it was Cliff Richard's "Never Say Die." I know.

And then I called 911.

The operator convinced me not to run out the back door... still hate her for that. So instead, I crawled under the console while some misguided human shot his way through the entire radio station, taking out the news room, the production room and then arrived in the On-Air studio. Things got a bit terrifying at this point...

I had the phone receiver in my hand, on the floor, under the board with the chord following me down... and the operator asking me what's going on, really? The dude is shooting up the entire booth, the vinyl albums, the transmitter, and the actual record on the air. Then I had an epiphany. While he was reloading his rifle, I realized that he couldn't shoot me while his gun was empty. I attribute this bit of knowledge to the fact that I was/am a James Bond, Mission Impossible, Starsky & Hutch, Rockford fan. See parents... let your kids watch the gun shows!

How I survived that night involved instinct yes, but also careful and slow reaction, along with kindness (to the gunman and the police who had their weapons drawn on my as I talked my way out of the building) and a deep, deep belief that my life was not going to end THAT night.

Here's to the 31 years of life since this ordeal... to thriving, not just surviving... and to really making the most out of it all while I'm here.

Passoni hit's 5K for her video

LET YOUR LOVE RISE - Fabiana Passoni

has a distinct sultry, voice and a fresh interpretive style. Her songs are a combination of jazz fusion with the older rhythms of Brazil such as bossa nova, baiao, and samba. Her intepretations are passionate, sensual and exciting.

The Geator Jerry Blavat climbs aboard The Drivetime Band Wagon

Click the icon for the original article.

DrivetimeUOJ Hit's the #1 slot on Reverbnation